The Leading Facts of American History: Chapter V: The Union.—National Development.—1789–1860.

V.

The Union.—National Development.—1789–1860.

217. Effect of the French and English War on the United States; The Leopard and the Chesapeake.—During all this time France and England continued at war. Each of these nations forbade the United States to trade with the other. This in itself was disastrous to our commerce; but, as if this was not enough, England insisted on stopping our vessels on the ocean and searching them for British sailors. Unless a man could prove that he was an American by birth, the English seized him—especially if he was an able-bodied seamen—and compelled him to enter their service. In this way they had helped themselves, in spite of our protests, to several thousand men, whom they forced to fight for them on board their ships of war. Finally (1807), the British man-of-war Leopard stopped the Chesapeake, one of our war-vessels, at a time when the latter could make no effectual resistance, and seized four of her men, one of whom they hanged as a deserter.

218. The Embargo and the Non-Intercourse Acts.—Congress passed the Embargo² Act (1807) to put an end to these outrages. The Embargo forbade any American vessel's sailing from one of our ports—even a fishing-smack found it difficult to leave Boston to get mackerel.³ Congress hoped that by stopping all trade with Europe we should starve France and England into treating us with respect.

But we did not starve them; our exports fell off forty millions of dollars in a single year, and the loss of trade caused great distress and discontent.

At last New England grew desperate; there seemed danger of rebellion, possibly of disunion, if the Embargo Act was not repealed. Congress did repeal it; and (1809) passed an act called the Non-Intercourse Act,¹ which forbade the people to trade with Great Britain and France, but gave them liberty to trade with other foreign countries. But though our exports rose, yet many men who had been engaged in commerce turned their attention now to manufacturing. This was one of the important results of the Non-Intercourse Act, since many of the manufactories of the country had their beginning at this time.²

James Madison.

223. Madison's Administration (Fourth President, Two Terms, 1809–1817); Re-opening of Trade with Great Britain.—When Madison¹ became President, Great Britain and France were actively at war, and our ships were still forbidden by Act of Congress² to trade with either country. The President was anxious to re-open commerce with one or both. The British minister³ at Washington gave Madison to understand that England would let our vessels sail the seas unmolested, if we would promise to send our wheat, rice, cotton, fish, and other exports to her and her friends, but refuse them to her enemy, France. The agreement was made. More than a thousand of our vessels, loaded with grain and other American products, were waiting impatiently for the President to grant them liberty to sail for Great Britain. He spoke the word, and they 'spread their white wings like a flock of long-imprisoned birds, and flew out to sea.' A great shout of joy went people from the people; farmers, merchants, ship-owners,—all believed that the fleet of vessels that had gone forth would return to fill thousands of empty pockets with welcome dollars. But England refused to carry out the agreement,—said it was all a mistake, as in truth it was,4 and so, to the disappointment and anger of multitudes, especially in New England, trade stopped as suddenly as it began.

224. How Napoleon deceived us.—Next, Napoleon, Emperor of the French, had a word of promise for us. He had seized and sold hundreds of our ships, because we would not aid him in his war against England. He now agreed to let our commerce alone, providing we would bind ourselves not to send any of our produce to Great Britain, but would let him and his friends have what they wanted to buy. Napoleon's offer was a trick to deceive us, and to get us into trouble with England. We agreed to his terms; he did not keep his word, and the ill-feeling between England and America was made more bitter than ever.

225. Tecumseh's Conspiracy; Battle of Tippecanoe.—Meanwhile, it was discovered that Tecumseh, a famous Indian chief, of Ohio, had succeeded in uniting the savage tribes of the West in a plot to drive out the white settlers. General Harrison, who became President thirty years later (1841), met the Indians at Tippecanoe, in the territory of Indiana, and defeated them in a great battle (1811). Tecumseh himself, however, was not in that battle; but he took a leading part in later ones, led by the English. Many Americans believed that England had secretly encouraged Tecumseh's plot. This belief helped to increase the desire of the majority for war with Great Britain.

226. The War of 1812; the Henry Letters; the Real Cause of the War; its Declaration.—It was still further increased by a man named Henry. He declared that the English government in Canada had employed him to endeavor to persuade the New England states to withdraw from the Union, and join themselves to Canada. In proof of what he alleged, he produced a package of letters, which he stated contained positive evidence of what he said. Madison paid Henry fifty thousand dollars for the letters. They were a fraud, and Henry was a villain; but for a time both the President and Congress were completely deceived by this artful swindler, and his letters made our hatred of Great Britain burn hotter than ever.

The real, final cause of the war, however, lay in the fact that England persisted in stopping our ships, taking American seamen out of them, and forcing them, under the sting of the lash, to enter her service and fight her battles.¹ This was an outrage that we could no longer bear—thousands of our citizens had been kidnapped in this way, and England refused to stop these acts of violence. For this reason Congress declared war, in the summer of 1812. New England, knowing that such a war would ruin what commerce she had, was opposed to fighting; but the rest of the country thought differently, and, with a hurrah for "Free Trade and Sailors' Rights,"² the war began.

227. Hull's March to Detroit; his Surrender.—Our plan was to attack Canada, and if all went well, to annex it. In expectation of the war, General William Hull had been ordered to march from Urbana, Ohio, to Detroit. Hull had served in the Revolution, and Washington had spoken of him as "an officer of great merit." In order to reach Detroit he had to build two hundred miles of road through forests and swamps. It was a tremendous piece of work. Hull did it, and reached Detroit. He did not get the news that we had declared war, until after the Canadians had got it, and had cut off most of the supplies of provisions and powder that he was expecting to receive. The forests back of Detroit were full of hostile savages; in front was the English general, Brock, with a force of Canadians and Indians. Brock summoned Hull to surrender. Without waiting to be attacked, without firing a single gun at the enemy, he hoisted a white table-cloth as a signal for Brock, gave up the fort, and with it Detroit and Michigan. For this act Hull was tried by a court of American army officers, convicted of cowardice, and sentence to be shot; but President Madison pardoned him on account of his services during the Revolution.¹

228. The Constitution and the Guerrière.²—But though we were beaten on land, we were wonderfully victorious at sea. England had been in the habit of treating America as though she owned the ocean from shore to shore. She had a magnificent navy of a thousand war-ships. We had twelve! One of our twelve was the Constitution, Captain Isaac Hull³—and certainly a braver officer never trod a ship's deck. While cruising in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, Captain Hull fell in with the British man-of-war, Guerrière. The fight began (August 19, 1812) without delay, and in twenty minutes the Guerrière surrendered, a shattered, helpless, sinking wreck.¹ The London Times said, 'Never before in the history of the world did an English frigate haul her colors to an American'; but before the war was over, England had practised hauling down her flag to Americans so much that it had ceased to excite surprise. Out of fifteen such battles, we won twelve. Captain Hull brought his prisoners to Boston. The Constitution, almost unhurt, and henceforth known as Old Ironsides,² was hailed with ringing cheers. Hull and his brave officers were feasted in Faneuil Hall; Congress voted him a gold medal for the victory, and gave his men fifty thousand dollars in prize money.

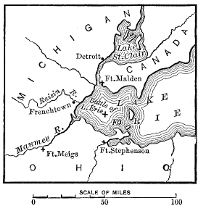

229. Progress of the War; Perry's Victory.—Later that year (1812), the Americans attacked Queenston, Canada, and General Harrison tried to drive the British out of Detroit, but nothing of note was accomplished.

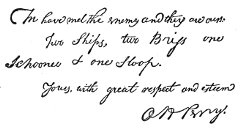

But in the autumn (September 10, 1813), Commodore Perry gained a grand victory on Lake Erie, near Sandusky, Ohio. Perry had gone to the shore of the lake, and, with the help of a gang of ship-carpenters, had built a little fleet of nine vessels from green timber cut in the wilderness back of them. With that fleet he captured the British fleet which carried more guns and more men. Before the fight began, he hoisted a flag over his vessel—the Lawrence—bearing the words, "Don't give up the ship."¹ During the battle, the Lawrence was literally cut to pieces, and her decks covered with dead and dying men. Perry saw that if he persisted in staying where he was, he must be defeated. Taking his little brother—a boy of twelve—with him, he jumped into a boat, and ordered the crew to pull for the Niagara. It was a perilous undertaking. The British shot broke the oars to pieces, and young Perry's cap was torn with bullets; but the boat reached the Niagara, and Perry gained the battle. When all was over, he sent this despatch to Congress, "We have met the enemy, and they are ours."

That victory gave us control of Lake Erie, and the British abandoned Detroit.

230. Jackson's Victory at Tohopeka.—The next year (1814) General Andrew Jackson—destined to be President of the United States—marched against the Creeks, a strong Indian tribe in the southwest territory, now forming the states of Alabama and Mississippi. The Creeks had fought against us from the beginning of the war; and the summer before Jackson set out to attack them they had massacred five hundred men, women, and children at Fort Mimms, near Mobile. Jackson was a man who never did things by halves. He drove the Indians before him, but at last they turned and met him (march 27, 1814) in battle at Tohopeka, or Horseshoe Bend, on a branch of the Alabama River. Here Jackson killed so many that he completely destroyed their power, and the result was that the Indians surrendered the greater part of their territory to the United States.

231. Battles of Chippewa and Lundy's Lane; Burning of Washington.—In the summer of the same year (1814) General Brown, with General Winfield Scott and General Ripley, gained the battle of Chippewa, in Canada (July 5, 1814). Later, they drove the British from a hard-fought field at Lundy's Lane (July 25, 1814), near Niagara Falls.

Meanwhile, the British had blockaded all our ports along the Atlantic coast, and had plundered and burned a number of towns. Later in the summer (August 24, 1814) they entered Washington. The sudden appearance of the enemy created a panic. President Madison fled in one direction; Mrs. Madison, filling her work-bag with silver spoons, snatched from the table, fled in another. The President's dinner, which had just been served, was captured and eaten by the enemy. After dinner, Admiral Cockburn, the English commander, and his officers, paid a visit to the House of Representatives. Springing into the Speaker's chair, he cried out, "Shall this harbor of Yankee Democracy be burned? All for it will say 'Aye!'" A general shout of "Aye!" "Aye!" settled the question. The torch was applied, and soon the evening sky was red with the glare of the flames, which consumed the Capitol, the President's House, and other public buildings. A recent English historian¹ says of that deed, "Few more shameful acts are recorded in our history; and it was the more shameful in that it was done under strict orders from the government at home."²

232. Macdonough's Victory on Lake Champlain; British Attack on Fort McHenry.—A few weeks after the burning of Washington, a British expedition fourteen hundred strong moved down from Canada by way of Lake Champlain to attack Northern New York. Commodore Macdonough had command of a small American fleet on the lake. A British fleet—carrying more guns and more men—attacked him (September 11, 1814) in Plattsburgh Bay.³ At the first broadside fired by the enemy, a young game-cock kept as a pet on board Macdonough's ship, the Saratoga flew up upon a gun; flapping his wings, he gave a crow of defiance that rang like the blast of the trumpet. Swinging their hats, Macdonough's men cheered the plucky bird again and again. He had foretold victory. That was enough. They went into the fight with such ardor, and managed their vessels with such skill, that in less than three hours all of the British ships that had not hauled down their flags were scudding to a place of safety as rapidly as possible. That ended the invasion from Canada.

The next British attack was on Baltimore, by the same force and fleet that had taken Washington. That city was guarded by Fort McHenry. All day and all the following night (September 13, 1814) the enemy's ships hammered away with shot and shell at the fort. Would it, could it, hold out? was the anxious question of the people of Baltimore. when the sun rose the next morning, the question was answered—"our flag was still there," the British had given up the attack, and were sailing down Chesapeake Bay. Baltimore was safe.

233. Jackson's Victory at New Orleans; End of the War.—Early the next year came the final battle of the war. The contest had now lasted over two years. The British determined to strike a tremendous blow at New Orleans. If successful, it might give them a foothold on the Mississippi River. Twelve thousand picked men under Sir Edward Pakenham made the attack (January 8, 1815). General Andrew Jackson defended the approach to the city with fortifications made of cotton-bales and banks of earth. He had just half as many men as the British commander, and they were men, too, who knew nothing of war.

In less than half an hour after the fight began, Pakenham was killed, and the enemy had lost so heavily that they gave up the battle. It was the end of the war. Great Britain had already made peace with our commissioners at Ghent, in Belgium (December 24, 1814); but as it often took even fast sailing-vessels a month or six weeks to cross the Atlantic, the news did not reach us until several weeks after Jackson's victory.¹ The treaty said nothing about the British claim of the right to search American vessels. There was hardly need to mention it, for our ships were no longer molested.

234. Results of the War.—The war, sometimes called "the second war for independence," had three chief results: 1. Though our military operations had generally been far from successful on land, yet we convinced Great Britain that we were able and determined to make our rights on the ocean respected. 2. The war showed foreign nations that any attempt to establish themselves on the territory of the United States was likely to end in disastrous failure. 3. By cutting off our foreign commerce for a number of years, the war caused us to build hundreds of cotton and woollen mills, thus making us to a much greater degree than before a manufacturing people—able to clothe ourselves, instead of having to depend on the looms of Great Britain for our calico and our broadcloth.

235. Summary.—Madison's administration was mainly taken up with the second war with Great Britain, begun in 1812 and ended early in 1815. The cause of the war was the refusal of England to stop seizing our sailors on board our ships and forcing them into her service. The war had the good effect of putting an end to this practice. That was nearly eighty years ago. Since then England and America have been at peace with each other. May that peace never again be broken!

² Embargo: an order by the government forbidding ships to leave port.

³ Coasting and fishing vessels might sail by special permission.

¹ Non-Intercourse: from Non, a Latin word meaning not; and Intercourse (here, meaning commerce or trade), hence a law forbidding trade.

² Later, Congress imposed new and heavier duties on many foreign goods, in order to enable the American makers to manufacture similar goods in this country, which it was thought they could not do at a profit if the foreign goods came in free.

¹ James Madison of Viginia and Alexander Hamilton of New York were the foremost of the distinguished statesmen who framed the Constitution and aided Washington in organizing the government. Madison not only drafted the main features of the Constitution, but offered the first ten amendments, adopted 1791.

Madison furthermore obtained the passage of the Religious Freedom Act of Virginia (originally drawn by Jefferson in 1778), 1785, by which entire religious liberty was granted, and all taxes for the support of public worship, and all religious tests for holding office in that state were forbidden. In this great reform, Virginia led every state not excepting Rhode Island, in some respects, and set an example followed in the Constitution of the United States (see Constitution, page xv, Paragraph 2). Madison was born in King George County, Va., in 1751; died 1836.

Madison (with George Clinton of New York, Vice-President) was elected President by the Republican, or Democratic, party (see Paragraph 199, and note 4).

² See Non-Intercourse Act, Paragraph 218.

³ Minister: see page 185, note 3.

4 It was the mistake of Mr. Erskine, the British minister.

¹ England's ground for seizing our sailors was that many of them were said to be deserters from her service, which was often true. She insisted that no British subject could become an American. This was at a time when she could not get her own people to enter her navy, and used to send gangs of sailors ashore in England at night, with hand-cuffs and gags, to seize men and drag them off to fight against France.

² By "Free Trade," we mean freedom to send our merchant ships to what ports we pleased; by "Sailor's Rights," we meant the protection of American seamen against seizure by the British.

¹ General Hull's defence was that he surrendered in order to save the women and children of Detroit from the scalping-knives of the Indians who formed part of Brock's force. James Freeman Clarke says, "Public opinion has long since revised this sentence [against Hull], and the best historians disapprove it."

² Guerrière (Ghĕ-re̅-air'). The British had captured this vessel from the French; hence her French name, meaning the Warrior.

³ He was nephew of General Hull.

¹ The Constitution carried on heavier guns and had the most men.

² See Holmes's poem on "Old Ironsides," written when it was proposed to break the old ship up, as unfit for further service.

¹ These were the last words of Captain James Lawrence (June 1, 1813), when he fell mortally wounded in a battle between his ship, the Chesapeake, and the English ship-of-war Shannon. Perry had given Lawrence's name to his ship.

¹ Green's "History of the English People"

² The English justified the burning of Washington on the ground that we had burned (May 1, 1813) the Canadian government buildings at York (now Toronto), then the capital of Canada. The truth is, that both sides perpetrated many acts which time should make both forgive and forget. ³See Map, page 213.

¹ It was on this occasion that Francis S. Key, of Baltimore, wrote "The Star-Spangled Banner." Key was a prisoner at the time on board of one of the British men-of-war. All night long he watched the bombardment of the fort. By the flash of the guns he could see our flag waving over it. In the morning, when the mist cleared away, he found it was "still there." His feelings of delight found expression in the song, which he hastily wrote in pencil on the back of an old letter. In a few weeks the people were singing it from one end of the country to the other.

While the news of the treaty of peace was on its way, a convention representing all of the New England states except Maine met in Hartford, in secret session. The enemies of New England declared that the object of the Hartford Convention was to dissolve the Union. Its real purpose was to adopt more efficient means of defence for the New England states, and to propose certain amendments to the Constitution.

![[Public Domain mark]](http://i.creativecommons.org/p/mark/1.0/88x31.png) Copyright/Licence: This work was published in 1922 or

earlier. It has therefore entered the public domain in the United States.

Copyright/Licence: This work was published in 1922 or

earlier. It has therefore entered the public domain in the United States.

![[Public Domain mark]](http://i.creativecommons.org/p/mark/1.0/88x31.png) Copyright/Licence:

The author or authors of this work died in 1964 or

earlier, and this work was first published no later than 1964.

Therefore, this work is in the public domain in Canada per sections 6 and 7

of the Copyright Act.

Copyright/Licence:

The author or authors of this work died in 1964 or

earlier, and this work was first published no later than 1964.

Therefore, this work is in the public domain in Canada per sections 6 and 7

of the Copyright Act.

![Homepage [Logo]](/images/logo.png)

![Map showing the location of the Tippecanoe Battle Ground [Map showing the location of the Tippecanoe Battle Ground]](/images/map_tippecanoe_leading_211_small.jpg)

![[Map of Great Lakes and St. Lawrence region] Map of Great Lakes and St. Lawrence region](/images/map_great_lakes_st._lawrence_leading_213_small.jpg)

![Battle of the Constitution and the Guerriere. [Battle of the Constitution and the Guerriere]](/images/battle_constitution_guerriere_leading_214_small.jpg)

![Don't give up the ship flag [Don't give up the ship flag]](/images/dont_give_up_the_ship_leading_215_small.jpg)

![Map of the South West Territory with battles of the War of 1812 highlighted [Map of the Southwest United States around the time of the War of 1812]](/images/map_southwest_leading_216_small.jpg)

![Map of the Niagara Frontier in the War of 1812 [Map of the Niagara Frontier during the War of 1812]](/images/map_niagara_frontier_leading_216_small.jpg)

![Map of the Potomac River and Chesapeake Bay region during the War of 1812. [Map of the Potomac River and Chesapeake Bay region during the War of 1812.]](/images/map_potomac_chesapeake_leading_217_small.jpg)